Friday, 18 October 2013

Jim Harrison, The Great Leader

It was up to each generation to be duped into lassitude by their own music.

Tuesday, 8 October 2013

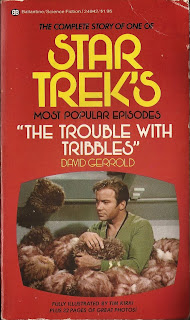

David Gerrold, On Creating A Tightly-Structured Plot

Irwin Blacker had taught a technique which I found very useful

now. Understand that every scene in a script is a confrontation

(either direct or indirect) between two or more people; the story can

be broken down into a series of one-line descriptions: “Spock tells

Kirk to use a better mouthwash. Kirk slugs Spock.” Put these on 3x5

cards and you have the whole story in front of you to shuffle around

as you choose.

The technique is especially helpful when you have two or more subplots to juggle, trying to fit them into a major plot. You can develop each plot line independent of the others and then assemble them for maximum impact and pacing. In this case, I was trying to build a story around the scenes depicting the fuzzies [Tribbles] breeding.

The first set of cards looked something like this:

Notice how the action builds toward a climax?

Having those cards to start with, then it is necessary to make up cards for the other elements of the plot and fit them in to see if they work.

At this point, a second set of cards is added:

This set of cards is shuffled into the pack and then perhaps a couple of extra scenes are written, scenes that are necessary to fill holes, smooth transitions, and provide necessary background material:

This technique can be called “Instant Story.” I know of no better method for breaking down a story into its component parts to see why it works—or, more often, why it doesn't work.

At this particular point in space and time, I had two thirds of my story. I had my major plot and I had one subplot masquerading as a major plot. Putting them on cards enabled me to see that I needed another subplot. I wasn't sure what it was yet, but I could see that I needed it. Later on, when I did realize what should go in the gaps, the cards would help me put them in the right places.

From "The Trouble With Tribbles" by David Gerrold

The technique is especially helpful when you have two or more subplots to juggle, trying to fit them into a major plot. You can develop each plot line independent of the others and then assemble them for maximum impact and pacing. In this case, I was trying to build a story around the scenes depicting the fuzzies [Tribbles] breeding.

The first set of cards looked something like this:

- Uhura is given fuzzy by Cyrano, implication that she will bring creature aboard ship.

- In Rec Room, Uhura's fuzzy has kittens. Second generation, eleven fuzzies. McCoy takes one.

- Third generation. 121 fuzzies. Establish that fuzzies are asexual—all of them can breed.

- Scene showing that fuzzies are starting to get out of hand. Fourth or fifth generation.

- Fuzzies in plague proportions. Kirk finds fuzzies in ship's stores, orders them off ship.

- Kirk finds fuzzies in grain. 1,771,561.

- Kirk makes Cyrano clean up fuzzies.

Notice how the action builds toward a climax?

Having those cards to start with, then it is necessary to make up cards for the other elements of the plot and fit them in to see if they work.

At this point, a second set of cards is added:

- Teaser: Enterprise answers emergency distress call.

- Distress call is false alarm. Kirk is annoyed at local official responsible. Start of a beautiful relationship.

- Kirk and local official have argument to dramatize the fact that they don't like each other.

- Kirk and local official have another argument, heightening tension between them.

- Local official is embarrassed at having assistant exposed as spy.

This set of cards is shuffled into the pack and then perhaps a couple of extra scenes are written, scenes that are necessary to fill holes, smooth transitions, and provide necessary background material:

- McCoy studies fuzzies, reports analysis of their biology.

- McCoy studies grain, reveals that it is poisoned.

- Tag. Uhura with fluff-ball earrings.

This technique can be called “Instant Story.” I know of no better method for breaking down a story into its component parts to see why it works—or, more often, why it doesn't work.

At this particular point in space and time, I had two thirds of my story. I had my major plot and I had one subplot masquerading as a major plot. Putting them on cards enabled me to see that I needed another subplot. I wasn't sure what it was yet, but I could see that I needed it. Later on, when I did realize what should go in the gaps, the cards would help me put them in the right places.

From "The Trouble With Tribbles" by David Gerrold

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)